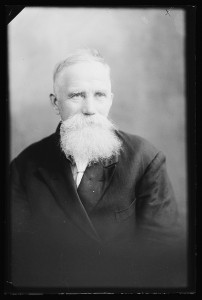

In honor of the excessive media coverage of the Boston Marathon bombings, I’ve decided to write this bog posting about an Arctic explorer named Paul Bjorvig (1857-1932). What does this virtually unknown Norwegian have to do with recent events in Boston? Absolutely nothing. That’s why I’m writing about him.

In 1898, Bjorvig took part in an American polar expedition led by two highly unlikely individuals, the Chicago journalist William Wellman and religious enthusiast Evelyn Baldwin. The expedition used Russia’s remote Franz Josef Land archipelago as a base for, among other things, searching for lost Norwegian balloonist Salomon Andree. Wellman and Baldwin also roamed about the archipelago. “We are giving the islands, straits, and points good American names,” Wellman wrote.While the two leaders were traveling around Franz Josef Land, Bjorvig and another Norwegian, Bernt Bentsen, remained behind in an ice cave and looked after the expedition’s supplies. Bentsen grew increasingly ill, perhaps from scurvy, perhaps trichinosis, and in January of 1899 he died. His last request to Bjorvig: “Please don’t let a polar bear eat my remains.” I promise you that I won’t, said his companion.

The only way to prevent a polar bear from dining on Bentsen was to keep his remains in the ice cave. A not very pleasant thought, but Bjorvig had given his word. He wrapped Bentsen in his, Bentsen’s, sleeping bag and, because the cave was so small, kept that sleeping bag right next to his own sleeping bag. Days blurred into weeks, but Bjorvig and Bentsen remained together, so to speak.

Eventually, Wellman returned to the ice cave (Baldwin was now inhabiting the crude Masonic lodge he’d built on Greely Island). Where’s Bentsen? he asked Bjorvig. “Dead,” Bjorvig replied, pointing to the sleeping bag. If he had then screamed in anguish or beaten his head against the cave’s icy wall, he might be remembered today, but he did nothing more dramatic than offer Wellman a cup of coffee.

In fact, the media — such as it was in those days — paid almost no attention to Bjorvig. Nowadays, of course, the media would swarm all over him, ramming microphones in his face and asking him all sorts of questions. What was it like to hang out with a dead man for two months? Did you contemplate suicide? Do you think the Arctic has conspired against you? How about your companion’s smell? Could you evaluate it on a scale of 1 to 10? And was it a threat to, if not your sanity, at least your appetite? In the end, Bjorvig would have become a celebrity and doubtless a talk show regular.

Once he returned to Norway, Bjorvig did not undergo a period of healing, nor did he engage in prayer or reflection. Instead, he signed up almost immediately for an expedition to Antarctica. After the Antarctic trip, he signed up for an expedition to Svalbard (Spitzbergen). While he was in Svalbard, he heard that his 22 year old son had been killed by a bear back in Norway. Not a single member of the media ever asked him how he felt about the loss of his son. At the time, such a question would have been considered vulgar if not downright invasive.

In 1908-1909, Bjorvig overwintered in Svalbard with his friend Knut Johnsen. One spring day the two men went for a walk, and Johnsen fell through the ice. There was nothing Bjorvig could do to save him. After his friend’s death, Bjorvig decided that (as he wrote in his journal) “I have had enough sorrow from the Arctic.” Then he added the following line:

But if a man has no sorrows, he has no joys.

Thanks to Perspektivet Museum (Norway) for the image of Paul Bjorvig, used under Creative Commons license.

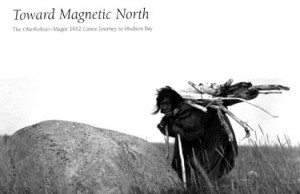

This extremely handsome book which includes photographs, diary jottings, and essays by various hands details explorer conservationist Ernest Oberholtzer’s epic 1912 canoe trip from The Pas, Manitoba, to Hudson Bay. The photos, especially, are remarkable; at once lyrical and austere, they provide an eloquent window on a lost time and a distant place. A “must” for canoeists and Arctic aficionados.

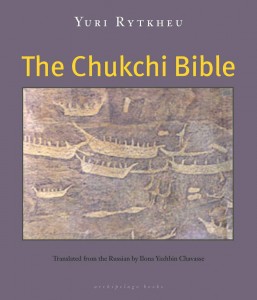

This extremely handsome book which includes photographs, diary jottings, and essays by various hands details explorer conservationist Ernest Oberholtzer’s epic 1912 canoe trip from The Pas, Manitoba, to Hudson Bay. The photos, especially, are remarkable; at once lyrical and austere, they provide an eloquent window on a lost time and a distant place. A “must” for canoeists and Arctic aficionados. Part myth, part fiction, and part family memoir, The Chukchi Bible details the history of Siberia’s Chukchi from the time when Raven created the world out of gobs of his own shit to the year 1999. But it’s not only a history. It’s also an elegy on the death of a traditional culture due to assaults from the outside world. I have no hesitation in calling the late Yuri Rytkheu’s book a master piece. Urgently recommended to anyone with even the slightest interest in the Arctic or its Native people.

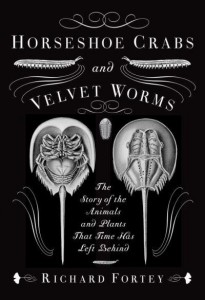

Part myth, part fiction, and part family memoir, The Chukchi Bible details the history of Siberia’s Chukchi from the time when Raven created the world out of gobs of his own shit to the year 1999. But it’s not only a history. It’s also an elegy on the death of a traditional culture due to assaults from the outside world. I have no hesitation in calling the late Yuri Rytkheu’s book a master piece. Urgently recommended to anyone with even the slightest interest in the Arctic or its Native people. Paleontologist Richard Fortey (author of Life: An Unauthorized Biography) rambles around the world in search of relic species, including onychophorans, gingko trees, lampreys, tuataras, chambered nautiluses, lungfish, ferrerets, horsetails, and echidnas. In his own home in England, he finds an ancient survivor known to everyone — the cockroach. Elegantly written and often very funny, this book provides an excellent complement to Piotr Naskrecki’s primarily photographic work Relics.

Paleontologist Richard Fortey (author of Life: An Unauthorized Biography) rambles around the world in search of relic species, including onychophorans, gingko trees, lampreys, tuataras, chambered nautiluses, lungfish, ferrerets, horsetails, and echidnas. In his own home in England, he finds an ancient survivor known to everyone — the cockroach. Elegantly written and often very funny, this book provides an excellent complement to Piotr Naskrecki’s primarily photographic work Relics.