On September 9, 2014, Parks Canada discovered the remains of the HMS Erebus, explorer Sir John Franklin’s remarkably newsworthy flagship. Among the artifacts retrieved from the ship was a Fortnum & Mason jar labelled “Sweets.” The jar did not contain any sweets, but rather a diary written by Sir John himself — a diary that solves at least part of the so-called Franklin mystery. What follows is that diary’s final entries:

April 30, 1847. Ship lies groaning & straining in the ice off King William Island. On a whim, I brought out my maps of Arctic Canada, only to discover that the Admiralty had provided me with maps of Polynesia — an unfortunate error.

April 30, 1847. Ship lies groaning & straining in the ice off King William Island. On a whim, I brought out my maps of Arctic Canada, only to discover that the Admiralty had provided me with maps of Polynesia — an unfortunate error.

May 2, 1847. Sore gums & loose teeth indicate that many of the crew have scurvy, so I spoke out against this nefarious French disease & initiated tango lessons and likewise bench pressing of the ship’s spittoons to ward it off.

May 3, 1847. Ship still mired in the ice. The bosun, in the midst of a tango maneuver, fell overboard, went through the ice, & was promptly torn to shreds by a school of man-eating isobars. Bloody Arctic!

May 5, 1847. Dreamt Lady Jane came for a visit & asked, “Sir John, why are you late to supper?” “I’m looking for the Northwest Passage, dear,” I told her. “But you can’t eat the Northwest Passage, can you?” she replied ominously, then vanished.

May 8, 1847. Lost three men today, one to scurvy, another to terminal gingivitis, & yet another to ennui. To make matters worse, the steward told me, in his inimitable fashion, “we ain’t got no more elevenses for you, sir.” How can I captain this expedition without my elevenses?

May 11, 1847. The cook extremely upset over our empty larders. Says there isn’t even any solder left inside our food tins. “Hang in there, old chap,” I told him, but the roar of the wind in the ship’s rigging garbled my words, & he tried to hang himself. At least the men are still obeying my orders.

May 12, 1847. Dense fog. We can’t even see the ship’s prow, much less a possible shortcut to the Orient.

May 14, 1847. We’re totally out of crumpets, so I had to feed Cedric [Cedric was Franklin’s pet toucan] a few forlorn scraps of hardtack. Not surprisingly, he squawked in protest.

May 15, 1847. Took bearings & discovered that, instead of corpulent, I am now merely portly. Remarkable that I can now ascend the mast-head as well as descend from it.

May 17, 1847. Men shivering almost constantly, & their beards are hung with icicles, as the Admiralty somehow has seen fit to supply us with tuxedos & cummerbunds rather than parkas. Wrote a letter of protest to the First Lord, then such was my hunger that I proceeded to eat it.

May 27, 1847. Several Savages [Eskimoes] with prognathous jaws visited the ship today. They brought us a batch of pemmican eggs. Alas, all rotten. Must have been laid before the great pemmican migration south. In return, we gave each of the Savages a tuxedo & cummerbund.

May 29, 1847. More misfortune — one of the crew, doubtless a petty officer, has eaten poor Cedric! I said to Fitzjames [Franklin’s second-in-command], “Find the bounder responsible for this & give him a taste of the cat.” “Sorry, sir,” Fitzjames told me, “but we’ve already eaten the ship’s cat.”

May 31, 1847. Lieutenant Orme, a clean-shaven fellow except for his clump of grizzled whiskers, broke into my cabin & consumed the contents of my chamber pot, then began singing “Rule, Brittania.” I put him in the section of the sick bay reserved for nutters.

June 5, 1847. Weary of being mired in ice, we abandoned ship & began making our way to Back’s Fish River, thence, we hope, to England’s green & pleasant land. The men carried me in a sedan chair. Two days into our journey, I realized I’d forgotten my robe & slippers, so we marched back to the ship.

June 8, 1847. Abandoned the ship a second time. Curiously, my sedan chair seems to have disappeared, & I’m now being manhauled in a sledge filled with towels, kettles, sail-maker’s palms, porcelain cups, bedding, checkerboards, our portative organ, longboats, etc.

June 9, 1847. Met a group of Savages & asked them using signs for the route to Back’s Fish River. They fled in terror when Fitzjames produced a loud blast of flatulence. “Sorry, sir,” he said, “but starvation seems not to agree with me.”

June 10, 1847. Longboats abandoned owing to the terrestrial aspect of the land.

June 12, 1847. Dr. Goodsir, our surgeon, tried to enliven things by asking us which vegetable the Admirably forbade us to take on board the Erebus. Answer: Leeks! Only Goodsir himself laughed at this feeble joke, & as he did, several of his teeth loosened in his gums, then fell into the snow.

June 13, 1847. What a nuisance! I seem to have left my monogrammed cutlery & all my medals on the Erebus, so we had no choice but to march back to the ship, which was now a sorry sight — both the fore & aft decks were covered with a thick coat of scurvy.

June 14, 1847. A blizzard has kept us on the ship, so I began working on a talk to be given tomorrow at tea-time. Key sentences include: Eat your boots, men. They’re quite tasty. Give me a nice fresh boot over steak-and-kidney pie any day. [On an earlier expedition, Franklin had been compelled to eat his boots]

June 15, 1847. Hallo, what’s this? Fitzjames has barged into my cabin without a knock. “Sir John,” he says, brandishing his cutlass, “the men & I have made an important decision. The cabin boy is lean & emaciated, while you…”

Here the diary necessarily breaks off, but the percipient reader will have no trouble ascertaining why Franklin’s remains have never been found.

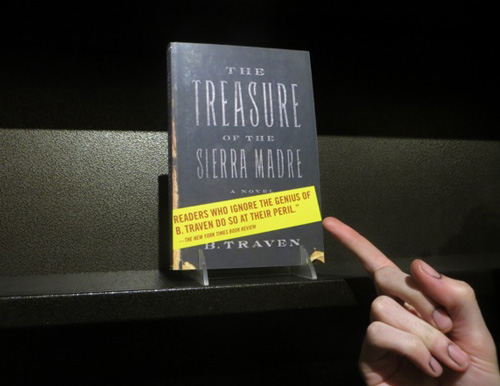

B. Traven was — and is — my favorite fiction writer. If you’ve seen the Humphrey Bogart film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, then you might know that the film is based on the Traven novel of the same name.

B. Traven was — and is — my favorite fiction writer. If you’ve seen the Humphrey Bogart film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, then you might know that the film is based on the Traven novel of the same name.

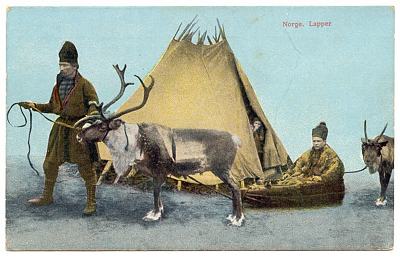

In the Middle Ages, Europeans had peculiar notions about Lapland. For instance, they thought all Samis (Lapps) were shamans. As it happens, many of them in fact were. Let’s say a sick person puts out a call for a noaidi (shaman). The noaidi would arrive at that person’s lodge in a reindeer-drawn sled. He would be obliged to enter via the chimney because the pile-up of snow prevents him from entering through the front door.

In the Middle Ages, Europeans had peculiar notions about Lapland. For instance, they thought all Samis (Lapps) were shamans. As it happens, many of them in fact were. Let’s say a sick person puts out a call for a noaidi (shaman). The noaidi would arrive at that person’s lodge in a reindeer-drawn sled. He would be obliged to enter via the chimney because the pile-up of snow prevents him from entering through the front door.