With a bog, you can write things that would be banned or at least censored elsewhere. Consider this particular posting. The editors to whom I proposed it some years ago rejected it so quickly that I didn’t have the chance to say that I never ate (perish the thought!) a wild dog (Lycaon pictus), but that my title simply paid homage to Ernest Seton Thompson, the estimable author of Wild Animals I Have Known.

If a sled dog in Greenland has outlived its usefulness, it can be useful again, as cuisine. In fact, the first dog I ever ate was a former Greenland sled dog. The hunter who offered it to me suggested that it was not nearly as good as seal. I had to agree. The meat was tough, stringy, and extremely greasy. It tasted not unlike the way a wet dog smells. Note: As the custom of using sled dogs declines in Greenland, so does the custom of eating them.

If a sled dog in Greenland has outlived its usefulness, it can be useful again, as cuisine. In fact, the first dog I ever ate was a former Greenland sled dog. The hunter who offered it to me suggested that it was not nearly as good as seal. I had to agree. The meat was tough, stringy, and extremely greasy. It tasted not unlike the way a wet dog smells. Note: As the custom of using sled dogs declines in Greenland, so does the custom of eating them.

On to the island of Pohnpei in Micronesia. If you see a teenage kid walking around with a baseball bat on Pohnpei, he’s not going to Little League practise. Rather, he’s looking for the island’s favorite feast food. Cooked in an umu (underground oven) and served without seasoning, Pohnpeian dog hardly tasted any better to me than Greenlandic dog. But De gustibus non disputandum est! The man seated next to me at the feast ate our entree with such gusto that no doubt he would have devoured Lassie or Rin Tin Tin had the occasion arisen.

In a restaurant on the Chinese island of Macau, I once ate a sweet-and-sour dog curry seasoned with noodles. The curry overwhelmed the meat so much that it tasted like sweet-and-sour ersatz. However, my host told me that the taste was not important. What was important, he said, was that the dish boosted one’s sluggish metabolism. Alas, my metabolism did not receive a spike or even a delicate nudge as a result of my having eaten the dish in question.

By far the best dog I’ve ever eaten was in a restaurant on the Indonesian island of Ambon. The animal had been raised on a “dog farm” as well as fed an exclusive diet of fruit. No kibble! Cooked in satay sauce, it tasted like high quality pork. I liked the dish (dare I call it a gourmet dish?) so much that I returned to the restaurant the following day and ordered it again. Here I might mention that only the island’s non-Muslims ate at this restaurant; for Muslims, dog is a prohibited meat.

How splendid that one person’s meat can be another’s poison! For if there were no differences in taste among different peoples in the world, the Golden Arches would be rising from every street corner instead of every fourth or fifth street corner.

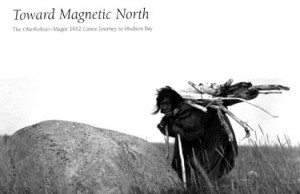

This extremely handsome book which includes photographs, diary jottings, and essays by various hands details explorer conservationist Ernest Oberholtzer’s epic 1912 canoe trip from The Pas, Manitoba, to Hudson Bay. The photos, especially, are remarkable; at once lyrical and austere, they provide an eloquent window on a lost time and a distant place. A “must” for canoeists and Arctic aficionados.

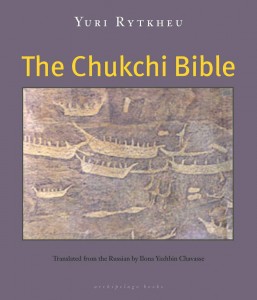

This extremely handsome book which includes photographs, diary jottings, and essays by various hands details explorer conservationist Ernest Oberholtzer’s epic 1912 canoe trip from The Pas, Manitoba, to Hudson Bay. The photos, especially, are remarkable; at once lyrical and austere, they provide an eloquent window on a lost time and a distant place. A “must” for canoeists and Arctic aficionados. Part myth, part fiction, and part family memoir, The Chukchi Bible details the history of Siberia’s Chukchi from the time when Raven created the world out of gobs of his own shit to the year 1999. But it’s not only a history. It’s also an elegy on the death of a traditional culture due to assaults from the outside world. I have no hesitation in calling the late Yuri Rytkheu’s book a master piece. Urgently recommended to anyone with even the slightest interest in the Arctic or its Native people.

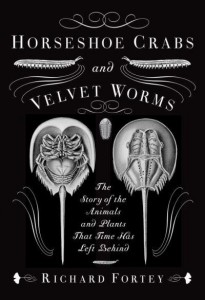

Part myth, part fiction, and part family memoir, The Chukchi Bible details the history of Siberia’s Chukchi from the time when Raven created the world out of gobs of his own shit to the year 1999. But it’s not only a history. It’s also an elegy on the death of a traditional culture due to assaults from the outside world. I have no hesitation in calling the late Yuri Rytkheu’s book a master piece. Urgently recommended to anyone with even the slightest interest in the Arctic or its Native people. Paleontologist Richard Fortey (author of Life: An Unauthorized Biography) rambles around the world in search of relic species, including onychophorans, gingko trees, lampreys, tuataras, chambered nautiluses, lungfish, ferrerets, horsetails, and echidnas. In his own home in England, he finds an ancient survivor known to everyone — the cockroach. Elegantly written and often very funny, this book provides an excellent complement to Piotr Naskrecki’s primarily photographic work Relics.

Paleontologist Richard Fortey (author of Life: An Unauthorized Biography) rambles around the world in search of relic species, including onychophorans, gingko trees, lampreys, tuataras, chambered nautiluses, lungfish, ferrerets, horsetails, and echidnas. In his own home in England, he finds an ancient survivor known to everyone — the cockroach. Elegantly written and often very funny, this book provides an excellent complement to Piotr Naskrecki’s primarily photographic work Relics.