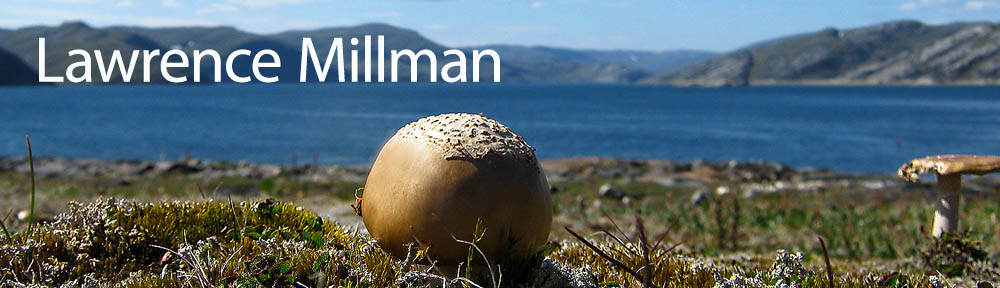

Mushrooms of the Pingualuit Crater Area

Fungi of the Pingualuit Crater region, Nunavik, Quebec, Canada

Collections and Photographs made in July 2008 by Lawrence Millman

In July of 2008, the government of Nunavik sponsored an environmental survey of the area around Pingualuit Crater, a 1,400,000 year old impact crater located in Pingualuit National Park in northern Quebec, Canada. In addition to writing several articles about Pingualuit Crater itself, I was asked to inventory the fungi in the vicinity of the Crater. Here are the results of that inventory.

Despite its subarctic latitude, the habitat around Pingualuit Crater resembles an arctic fell field considerably more than it resembles a botanically richer subarctic environment. As a result, lichens tend to be the dominant form of vegetation. Most rocks within 2 kilometers of the Crater have some sort of lichen species growing on them; and much of the ground cover between these rocks has been colonized by lichen, especially fruticose lichens of the Cladina genus.

Thus it’s not surprising that the most common fungi in the vicinity of the Crater have an obligate lichen association. Lichenomphalia ericetorum is a pale yellow species that grows with the small bright green lichen Botrydina vulgaris. Also associated with B. vulgaris is Omphalina luteovitellina, a more brightly yellow or orange species. Lichenomphalia hudsonii typically grows with the leaf-shaped lichen Corsicum viride.

Most of the other fungal species are mycorrhizal, which means that their mycelium has established an exchange of nutrients with the rootlets of plants. Such species include: Amanita inaurata, growing with Salix herbacea; Cortinarius vibratilis, also growing with S. herbacea; and Laccaria bicolor, growing near the airstrip and probably associated with a sedge. As an adaptation to strong winds and cold conditions, these species exhibit a more compact morphology (shorter stipes and caps hugging the ground — see photo of Russula silvicola) than the same species in less northern habitats.

One of the few species I found that neither associates with a lichen or forms a symbiotic relationship with a plant is Lycoperdon umbrinum. Frequently, this puffball grows where the vegetative substrate has been worn away by human action — i. e., in disturbed places. As it happens, I found L. umbrinum in the only equivalent to this type of habitat inside the Crater — on the section of the western slope that’s commonly used for access by scientists and Park personnel.

Since my visit to the Crater was probably a few weeks too early for optimal fungal fruitings, the species count in my inventory is relatively low. If I had made a later visit, I suspect I would have found more species in the same genera — especially more Lichenomphalia and more Cortinarius. For a particular habitat determines its particular fungi.

Species Inventory:

- Amanita inaurata (=ceciliae)

- Cortinarius croceus

- Cortinarius rubellus

- Cortinarius vibratilis

- Laccaria bicolor

- Lactarius hepaticus

- Lactarius uvidus

- Lichenomphalia (=Phytoconia) ericetorum

- Lichenomphalia (=Phytoconia) hudsonii

- Lichenomphalia (=Phytoconia) umbellifera

- Lycoperdon umbrinum

- Omphalina luteovitellina

- Russula silvicola

- Russula variata

You might also enjoy reading about the Fungi of Kuujjuaq.