Not so long ago, I was visiting a stamp-collecting friend, and I happened to see the corticioid species Terana caerulea on a recent Macedonian stamp. A corticioid fungus on a stamp?? I was beside myself with astonishment, since corticioids (aka, crusts) are the outsiders of the fungal world, either despised or ignored. A mycophile of my acquaintance refers to them as “molds.”

Not so long ago, I was visiting a stamp-collecting friend, and I happened to see the corticioid species Terana caerulea on a recent Macedonian stamp. A corticioid fungus on a stamp?? I was beside myself with astonishment, since corticioids (aka, crusts) are the outsiders of the fungal world, either despised or ignored. A mycophile of my acquaintance refers to them as “molds.”

There’s no reason to despise Terana caerulea, however. The name of its former genus, Pulcherricium, will tell you why. The species is an intense cobalt blue when fresh and a pleasant bluish color when not so fresh. Even the spores are bluish in color. The surface is smooth or slightly tuberculate, with a waxlike consistency. Inhabiting hardwood debris, T. caerulea can be found in New England, although it’s far more common in the southeastern part of the country.

Here’s my hope: that other countries will start putting crust fungi on their stamps, and in this way help to stamp out a more or less worldwide prejudice. I can imagine the bright-red Phanerochaete sanguinea on a Seychelles stamp and the wine-red Cytidia salicina on a Tunisian stamp. I can also imagine the yellow hydnoid Mucronella flava on a Serbian stamp and the green-blue Byssocorticium atrovirens on a Danish stamp.

Dare I hope that America, perhaps the most anti-corticioid of all nations, will put a (for example) gold-yellow Lindteria trachyspora on one of its stamps?

Photograph by Brian Luther.

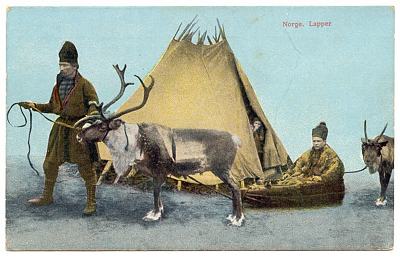

In the Middle Ages, Europeans had peculiar notions about Lapland. For instance, they thought all Samis (Lapps) were shamans. As it happens, many of them in fact were. Let’s say a sick person puts out a call for a noaidi (shaman). The noaidi would arrive at that person’s lodge in a reindeer-drawn sled. He would be obliged to enter via the chimney because the pile-up of snow prevents him from entering through the front door.

In the Middle Ages, Europeans had peculiar notions about Lapland. For instance, they thought all Samis (Lapps) were shamans. As it happens, many of them in fact were. Let’s say a sick person puts out a call for a noaidi (shaman). The noaidi would arrive at that person’s lodge in a reindeer-drawn sled. He would be obliged to enter via the chimney because the pile-up of snow prevents him from entering through the front door.